When I first started watching unscripted television back in the Y2K Times (it’s no coincidence to me that reality TV and the rise of the mainstream internet occurred in tandem!), it quickly became uncommon for any participant to even acknowledge that they were “on a show” – that would break the fiction.

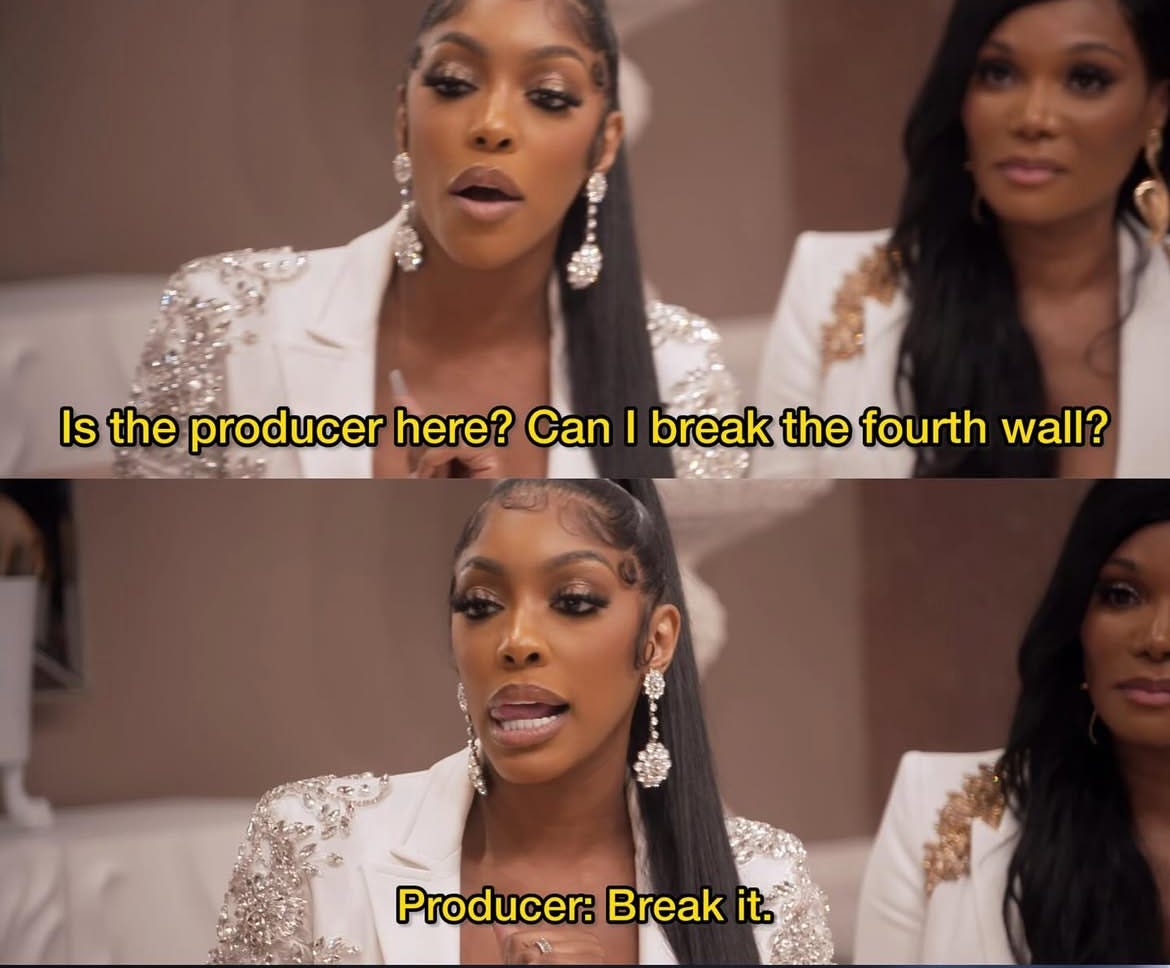

Now, I’m seeing this concession everywhere – the stress of public scrutiny, social media behavior, and the way participants themselves try to slip the yoke of production becomes a key component of each participant’s Experiment, to where it is more interesting to acknowledge it than to ignore it.

As we discussed last time, the border between the 'real' world and the imaginary circumstance is becoming part of the story. To a game designer like me, and like lots of you reading, this is super interesting – the players essentially improvise their own rules, and viewers implicitly decide on how appealing or permissible those improvisations are.

Phones, social media profiles and viewer-followers are also crossing into the fictional reality more and more – instead of pretending participants are totally isolated from such things, production now seems to acknowledge that any contemporary relationship where there’s no Instagram, and therefore no fights about who your boyfriend is ‘liking’ on Instagram, is just not realistic any more.

Let’s look at some examples!

Wedding show participants often develop eyes for a participant in a different couple – but most shows used to quash love triangles (“this isn’t Wife Swap” was a go-to phrase) in favor of preserving the sanctity of the fiction. Nobody fights it any more, because viewers absolutely love that type of scandalous shit. In fact, ‘participant is secretly messaging someone other than their partner’ has become a regular story beat that I suspect producers even nudge into being.

The “real world” (life online) is virtually impossible to keep out of Experiment fiction. The most recent season of LiB has a woman who was sure her match had followed her on Instagram prior to meeting her “sight unseen” in the pods and therefore already knew what she looked like. Season 12 of MAFS Australia, currently airing in the UK, has not one but two couples who, upon arriving at the altar, had actually already dated their “surprise” match. One guy got dumped from Love is Blind because the woman he was interested in was too suspicious of how “scripted and rehearsed” his romantic style seemed.

Love is Blind’s “Disaster Dave” derailed his entire relationship by obsessing over interactions his partner had with someone he tangentially knew, long before she came on the show. He later said he regretted this fixation, and that the outside individual had clearly been trying to grab his fifteen minutes of fame by association. “We were warned [by producers] about people like that,” he said at the reunion, who “mess around with people’s relationships just because [they] want to be on Netflix.”

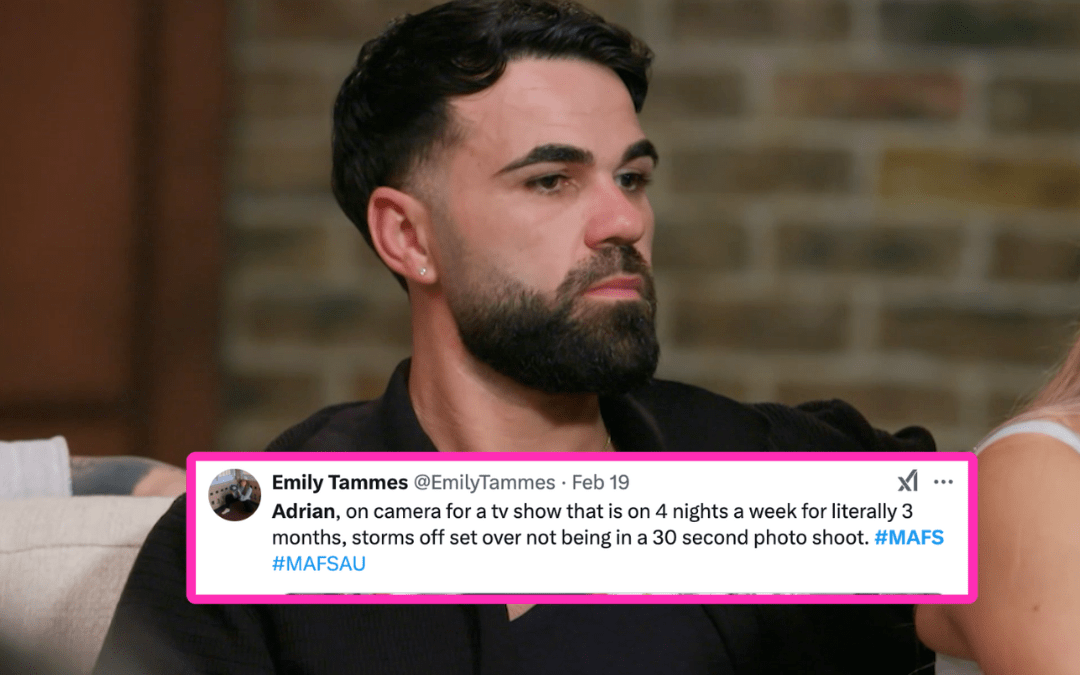

On a recent season of MAFS Australia, one groom walked out on his bride because he wasn’t featured in a production promo for the show — a direct acknowledgment of his motive for fame. Another walked off the set within the first three days of his “honeymoon” because his bride was over the age of 25 and said she wanted only one child instead of three or four. Behavior that might have once been a disaster for romantic narratives is now part of the game for the producers – who have been giving both these grooms hilariously vicious edits as if to punish their recalcitrance. In one case, production even surfaced a groom’s audition tape to point out contrasts in how open-minded he said he would be versus the roadblocks he placed once filming began.

In a more transparent and voluntary filming environment, the ‘gaminess’ of unscripted TV becomes much more plainly enjoyable. It resembles nothing more to me than watching a good DM and a group of clever roleplayers – a DM should not allow players to break rules willy-nilly or run away with the whole campaign, but a good DM finds ways to accommodate players’ natural personalities and inclinations in their story plan, even when those are disruptive.

Being on a reality show seems a lot like roleplaying as oneself, as a job, while the producers shape the campaign toward the interests of a viewing audience they know very well. It’s endlessly fascinating stuff, if you ask me.

If you think so too, please share this article and subscribe to this Substack – as always, the content economy ain’t what it used to be and your support in helping this series gain reach is priceless to me. If you want to support this ongoing body of work linking reality television and game design of all stripes, your paid subscriptions, whatever you wanna pay, are warmly appreciated.

Next time: What makes a ‘great’ reality star? Hint: One of them is president of the US right now.

"Being on a reality show seems a lot like roleplaying as oneself, as a job, while the producers shape the campaign toward the interests of a viewing audience they know very well."

See, I'd be fascinated to see more reality TV that was geared towards this sort of exaggerated performance -- somewhere between pro-wrestling personas and a game show.

But so much of reality TV leaves me cold because I'm completely uninterested in romance/sex content (particularly when they're mined for conflict and disaster).